A pang of indecision shuddered within me when my twelve-year-old daughter came home with her 7th grade summer reading list, excitedly proclaiming that she would be reading The Hobbit.

“How old were you when you first read it?” she asked.

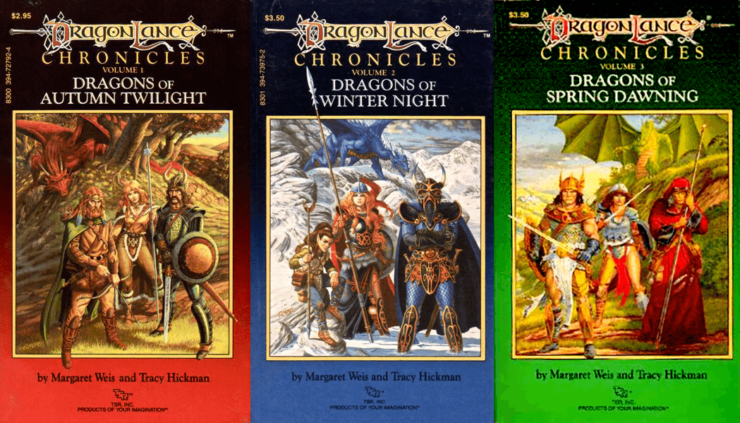

I swallowed and loosened my collar. Once again, I imagined I was back in junior high with Tolkien’s masterpiece in one hand and, in the other, a beat-up paperback of something my older brother had read called Dragonlance. It’s been a choice I have long agonized over, as I have raised my daughters on a healthy diet of Tolkien admiration. He made up entire languages, girls! Let’s examine his novels’ religious subtext! Hey, who wants to watch the movies for the 17th time?

Yet deep down inside, I know the truth.

I read Dragonlance first.

If you’re not a child of the 80s or 90s and have no idea what in the world I’m talking about, there’s a long-simmering criticism that Margaret Weis and Tracy Hickman’s blockbuster Dragonlance novels were a rip off of Tolkien’s work and basically a long role playing game that bled onto pages that millions of people read.

I’m not going to get into that debate, as Tolkien’s trolls that tried to have Bilbo and the dwarves for dinner have nothing on the real ones sitting in front of their computers, their fingers ready to make snarky comments about politics, religion, and fantasy literature.

So, I’m going to let the haters do their thing and focus on what I know to be true: I do not regret choosing Dragonlance as my foray into fantasy.

Let’s put it this way: I haven’t re-read the Dragonlance novels in probably twenty years, and I remember more about the characters than I do most of the people I went to high school with.

Dragonlance imprinted on me not only because it was my first epic fantasy, but because many of the characters were deeply flawed and often failed miserably. They were a rag-tag group of friends, scorned even in their town. As the hero of the novels, Tanis Half-Elven, once stated of his companions, “We are not the stuff of heroes.”

And he’s right. All the heroes—representing all your favorite fantasy tropes—have issues. Tanis is right there at the top, struggling with his heritage and that he’s the product of a rape of an elf by a human. It’s further complicated by his love for two women (an elf and a human—I told you he had issues), and near the end of the novel, he betrays the friends who’ve followed across the apocalyptic landscape of Krynn and must attempt redemption.

Speaking of Tanis’ loves, long before Sansa Stark became everybody’s favorite royal-turned-politician-turned-ruler, there was Laurana. She first appears as a spoiled elven princess clinging to her childhood crush, but when Tanis rebuffs her, she learns what it is to survive in the harsh world outside her privileged bubble, dusting herself off from repeated defeats, rising when others crumble before becoming the general of armies herself.

But none of the companions come close to needing a therapist more than Raistlin, the sickly mage who becomes the classic anti-hero. It doesn’t help that the poor kid has hourglass eyes. Bitter and sarcastic, with a handsome twin brother who looks like a young Arnold Schwarzenegger, he delivers some of the best scenes on the novels with the compassion he shows to other outcast creatures. The question of whether or not he is good or evil bounces back and forth until the end, when Raistlin truly gets the last (frightening) laugh.

And then there’s the true star of the books: the world itself. A cataclysm has upended Krynn, turning once majestic cities into crumbled disasters. The cause of the cataclysm is a major theme in the novels: how power corrupts. It falls to the everyday people, the skillet-wielding waitress and other blue-collars of the fantasy world, to try and fight again the encroaching night.

It’s a bit of a spoiler, but Dragonlance presented one of the great lessons of life to me as budding adult: that evil turns upon itself. Good doesn’t really triumph; evil just betrays its own.

And from the original Dragonlance Chronicles came seventeen million (at least it looked that way in the paperback section of Bookland) spinoff books, but do yourself a favor and read the companion trilogy about Raistlin and his brother. It’s a thrill to watch the twins battle and grow, becoming men who come to understand the darkness within them both.

From that spawned my lifelong love affair with fantasy. I made my way to Terry Brooks, to David Anthony Durham and Greg Keyes and Neil Gaiman. And, as we established earlier, a devotion to Tolkien.

Dragonlance even impacted me, thirty years later, when I published by first novel and something kept toying at me not to make my protagonist the expected hero. It just didn’t seem right that she’d be a brilliant district attorney, a tenacious reporter, or a scrappy cop.

Instead, she would be a grandmother, largely relegated to serving as a support system for her family when her grandson mysteriously vanishes and no one, from police to the FBI, can find him. Yet as the story progresses, it is this unassuming woman who truly finds the answers that may, at last, rescue her grandson from an other-worldly plight.

She makes mistakes. She has dark secrets. She is terrified and almost gives up. She is not, as Tanis Half-Elven said, the stuff of heroes.

From the very beginning, Dragonlance showed me that’s exactly who should be saving our worlds.

Originally published July 2019

Jeremy Finley’s investigative reporting has resulted in criminal convictions, legislative hearings before the U.S. Congress, the payout of more than a million dollars to scam victims, and the discovery of missing girls. The winner of twenty Emmys and Edward R. Murrow awards, he is also the recipient of a national Headliner award, a two-time winner of the IRE award (recognizing the best in investigative journalism) and a national Edward R. Murrow award. In 2016, he was named the journalist of the year by the Tennessee Associated Press. He is the chief investigative reporter at the NBC affiliate in Nashville, TN, where he lives with his wife, daughters, and Thor, the worst puppy on the planet. The Darkest Time of Night and its sequel The Dark Above are available from St Martin’s Press.